Among the less-discussed deprivations of this past year has been a reduction of opportunities for listening to the music of the repressed Soviet avant-garde.

Before the lockdowns, when my children went to school, I had a lot of time to myself. There was always work to do — lectures to prepare, articles to write, e-mails to return — but after a few hours I would get distracted and put on an episode of Columbo or rearrange the books in my office. To get myself to concentrate, I used to listen to the radio; that is how I heard Sergei Protopopov’s “Second Piano Sonata”.

The piece might be described as “grinding” or “mechanical”, “like chewing on broken glass,” yet it touched me somehow — as if an adding machine had been made to sing about heartbreak. (Such things aren’t often played on radio, but WKCR in New York is run by volunteers with a lofty disregard for the listener’s enjoyment. They have played worse.)

I bought a recording of the Second Sonata, and another of the Third — I could not find the First — and I would put them on in the lonely lulls of the afternoon.

Now my children are home most afternoons, and they do not like these recordings. The reason is that they like to listen to “music that sounds good” as opposed to “very bad”. So when they are home we listen to Bach or sometimes Debussy. We do not listen to Roslavets or Avraamov or Vyshnegradsky (that god among men) — or Protopopov.

To compensate for these losses and a growing sense of embourgeoisement, I thought I might at least read something on Protopopov — who he was, what he was trying to accomplish.

I found a book called Music of the Repressed Russian Avant-Garde, 1900-1929 by the Australian composer Larry Sitsky. Sitsky describes Protopopov as

a close, perhaps even fanatic adherent to the Yavorsky system […]. [H]is music is a species of practical demonstration of the theory. The sonatas […] are marked by a great exuberance and extravagance, clearly derived from late Scriabin, but because of Protopopov’s slavish adherence to the above theory, they suffer from a uniformity of harmonic fields […]; sometimes they seem almost endless. […]

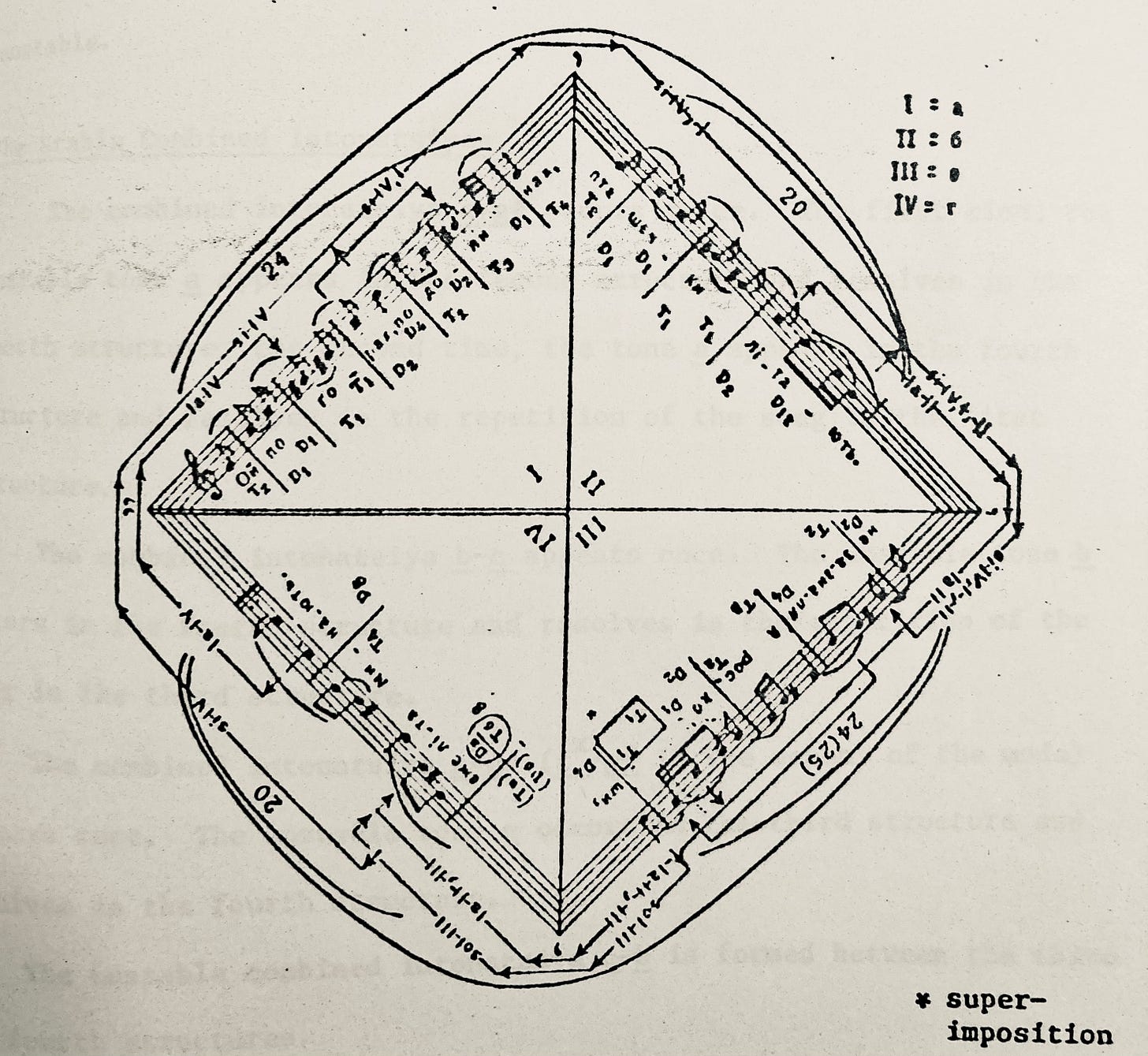

I will not try to explain the Yavorsky system; I do not understand it. (Representative excerpt: “The first intonatsiya occurs owing to the combined intonatsiyas A-G and F#-G. The first intonatsiya is composite, formed from two intonatsiyas: a) plagal A-G, and b) authentic F#-G. The second intonatsiya is plagal.”) But Sitsky is right that Protopopov was an “adherent”. He had studied under Yavorsky; his first two piano sonatas are dedicated to Yavorsky; his book — The Elements of the Structure of Musical Speech — is a summary of Yavorsky’s musical theories.

This book, like the music, is grinding and mechanical and somehow affecting. This is from a discussion of a folk song called “Oy po gorakh” (“Oh, through the mountains”):

As a whole the song in unstable.

The song is solo.

The cycle is personal life (the female lot).

The genre is narrative.

The character is drawn-out.

The book does not seem to have been well received. In 1931, when it was authorized by the State Music Publishers on the grounds that “The proletariat in the historical development of its dictatorship is mastering all forms of ideological superstructures including its music,” the theory was deemed “undoubtedly debatable”.

A year later, the debate was over; according to Sitsky, “the theory was found to be insufficiently Marxist. […] After this […], Protopopov’s book and his career as a composer, fell into obscurity.” He had written three piano sonatas and a dozen songs.

In his dissertation on The Elements of Musical Speech, the musicologist Gordon McQuere says the shape of Protopopov’s life “is almost impossible” to trace.

While he is often mentioned as one of Yavorsky’s most important pupils, he is seldom mentioned for his own merits. He was born in 1890 and began to study with Yavorksy at the Gelman music school in Moscow in 1913. […] While their official relationship occurred from 1913 to 1921 in Moscow and Kiev, a large body of correspondence exists from various years thereafter. Protopopov was in Saratov at the time of Yavorsky’s death. The date of Protopopov’s death, 1954, was discovered only in a footnote to an introductory note to the Yavorsky collection, where has is credited with a great deal of work in the organization of Yavorksy’s papers, which had been left in disarray.

But then more details of his life emerged.

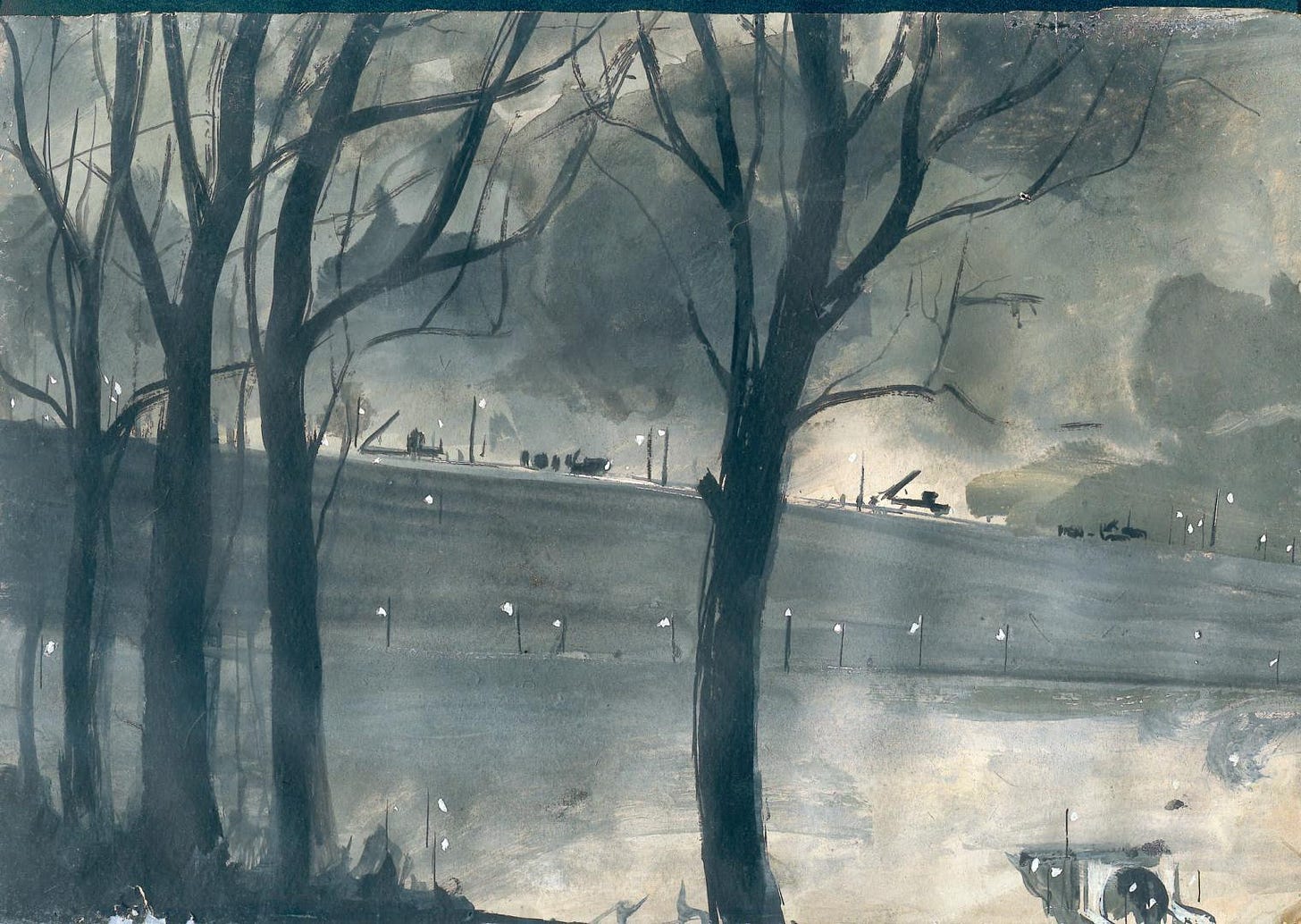

A few years ago, the musicologist Inna Klause discovered that Protopopov had been a prisoner of the Interior Ministry from 1934 to 1936 — first in Eastern Siberia, and then at the Dmitrovsky Correctional Labor Camp (or “Dmitlag”) near Moscow.

Dmitlag was the largest correctional labor camp in the Soviet Union. Its main purpose was to dig an 80-mile canal — now called the Moscow Canal — connecting the Moskva River with the Volga. But a secondary purpose was the social and spiritual improvement of its 192,649 prisoners — if not in reality, then at least to the satisfaction of the Interior Ministry. Camp administrators organized a theater, libraries, political meetings, newspapers, magazines, athletic events and concerts.

In 1936 a songwriting competition was held in order that — as the camp “music inspector” put it — the “canal soldiers” might have occasion “to express the happiness which life in the Stalinist epoch entails, in which we live joyfully as the work goes on.”

In the end, 73 prisoners entered 112 pieces in the competition; these were judged by some of the most prominent composers in the Soviet Union — Ivan Dzerzhinsky, Viktor Bely and Dmitri Kabalevsky among others. (According to the camp newspaper, Shostakovich — though not an official member of the jury — was given a number of entries to review and found them “all of a high level”.)

First prize of 500 rubles was given to the “March of the Concrete Workers”, by a prisoner called Nikolai Cedric. But — as Inna Klause notes — in the announcement of this result, the prisoner “Sergei Ivanovich Protopopov” was also commended “For his active participation in the recording of the songs of the canal soldiers and for good musical work” as well as a “complicated technique”; he was given a badge and 100 rubles.

Klause infers from this that the competition was “a fiction”. Evidently Protopopov — with help from another prisoner, the pianist Aleksandr Rozanov — had not only recorded most of the entries in the competition, but had actually written many of them himself — including at least some of the music for “The March of the Concrete Workers”. Probably it was too much to hope that 73 untrained prisoners, forced to dig a canal, would spontaneously begin to compose hymns to the happiness which life in Stalinist Russia entails. Fortunately for everyone, Protopopov was there.

But why was he there?

Although Sitsky and others assumed he had fallen out of favor with the regime for some form of musical deviationism or other, what Klause found was simpler and sadder. On April 4, 1934, a special committee of the Soviet secret police had convicted him, in a secret process, of “homosexual acts”.

The words “homosexual acts” were presumably chosen to fit the text of a December 1933 ruling of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union outlawing such things. But the facts are that Protopopov was in love; that he had been living with the only man he loved, and would love, for his entire adult life; and that this man was Boleslav Yavorsky.

It is not clear why Yavorsky too was not imprisoned for “homosexual acts”. Possibly he was protected by his greater fame. In any case, his relationship with Protopopov continued even after the arrest and deportation; and when Protopopov was brought to Dmitlag in 1936, Yavorsky came to see him twice under the pretext of a concert for the prisoners. (Both concerts included music of Protopopov.)

And there is every reason to think the relationship continued, in some form, until Yavorsky’s death in 1942.

As a prisoner in Siberia, Protopopov set several Russian folk songs to music, including “Proshchay zhizhn’” (“Farewell, Life”):

Farewell, life, farewell, my joy — oh!

I hear you going away from me, my love — oh!

I hear you going away from me.

I hear you going away from me, my love — oh!

It is our fate, my love, we must be parted,

Nevermore will I see you again.

I want to say that Protopopov’s great theme was not “the Yavorsky system” but Yavorsky himself; not slavish adherence but true love. But sometimes it is hard to tell the difference.